The Journal of Values-Based Leadership The Journal of Values-Based Leadership

Volume 8

Issue 2

Summer/Fall 2015

Article 3

July 2015

Universalism and Utilitarianism: An Evaluation of Two Popular Universalism and Utilitarianism: An Evaluation of Two Popular

Moral Theories in Business Decision Making Moral Theories in Business Decision Making

Joan Marques

Woodbury University

, joan.marques@woodbury.edu

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl

Part of the Business Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Marques, Joan (2015) "Universalism and Utilitarianism: An Evaluation of Two Popular Moral Theories in

Business Decision Making,"

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership

: Vol. 8 : Iss. 2 , Article 3.

Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol8/iss2/3

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been

accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar.

For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected].

1

Universalism and

Utilitarianism: An

Evaluation of Two

Popular Moral

Theories in

Business Decision

Making

Introduction

Moral theories are interesting phenomena. There are overlapping, complementary and

contrasting theories: rigid, temperate, and flexible ones and ancient and more

contemporary-based ones. Regardless, they all make sense when

perceived against certain backgrounds, circumstances, and

mindsets. The above may already indicate that moral theories — and

therefore the decisions made with these theories as guidelines —

can be confusing. It should also be stated that business leaders —

especially those who did not attend college — base their moral

decisions more on “gut feelings” than anything else. As has been

stated by many sources, they may simply be going by the “quick and

dirty” moral self-test of asking themselves whether they would mind

if their decision made it to the front page of tomorrow’s newspaper

or if their family would know about it. A third option might be to

consider whether they would want their child (or other loved one) to

be on the receiving end of this decision.

There are various theories embedded in these quick deliberations: the Golden Rule (which

states that we should not do unto others what we would not have done unto ourselves)

comes to mind, especially in the last instance. A leader who would not want a loved one to

be on the receiving end of her decision has deliberately or reflexively included the notion of

not wanting to do unto others what she would not have wanted to be done unto herself (or

her loved ones). We can also find a sprinkle of Universalist thinking in this deliberation as

placing a loved one into the picture immediately eliminates the use of any party as a mere

means toward a selfish end. There are undoubtedly more moral theories to be detected into

the above contemplations (e.g., the character-based virtue theory), but in order to remain

focused on the purpose of this paper, this should do.

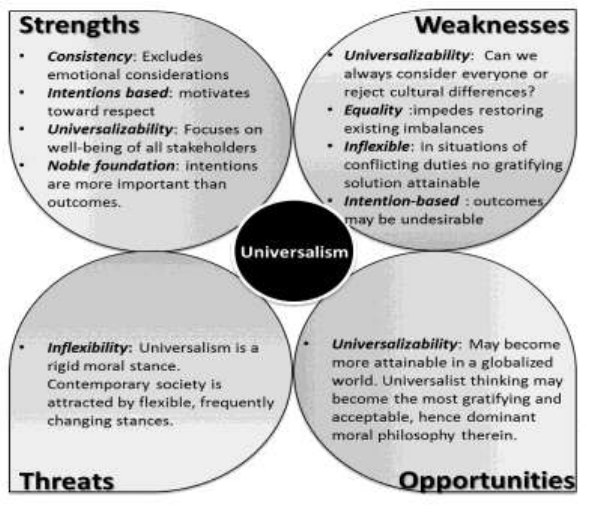

The purpose of this paper is to underscore the complexity of making moral decisions by

discussing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of two high-profile

theories: Universalism and Utilitarianism. The reason for selecting Universalism and

Moral theories remain a topic of interest, not just to moral

philosophers, but increasingly in business circles as well,

thanks to a tainted reputation that urges more awareness

in this regard. Based on the expressed preferences of 163

undergraduate and graduate students of business ethics,

this article briefly examines the two most popular theories,

Universalism (Kantian) and Utilitarianism

(consequentialist), and presents a SWOT analysis of both.

Some of the strengths and weaknesses that will be

discussed for Universalism are consistency, intension

basis, and universalizability, while some of the discussed

strengths and weaknesses for Utilitarianism are flexibility,

outcome-basis, and lack of consistency. Subsequently,

some common factors and discrepancies between the two

theories will be discussed. In the conclusive section, some

suggestions and recommendations are presented.

JOAN MARQUES, PHD, EDD

BURBANK, CALIFORNIA

2

Utilitarianism is explained infra. The paper first provides a brief discussion of the two

selected moral theories and subsequently analyzes the strengths and weaknesses inherent

to each theory. It is then followed by the opportunities and threats they may present.

Subsequently, some common factors of — and discrepancies between — the two theories

are discussed. In the conclusive section, several suggestions and recommendations are

presented.

Why These Two Theories?

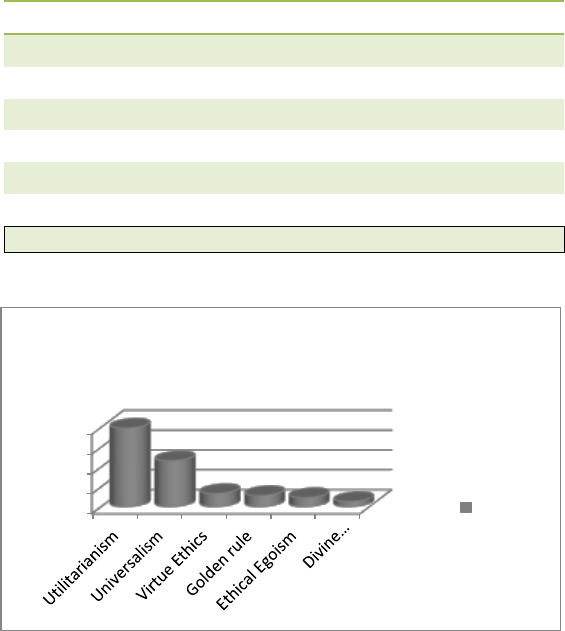

Over the course of 6 semesters, the author of this paper, a facilitator of Ethics-based

courses for undergraduate and graduate business students, found that, from the 163

students who finished the courses, there was a clear preference for the two theories to be

discussed. In the courses, these students were exposed to multiple moral theories and

encouraged to research the theory that appealed mostly to them. They were given cases and

scenarios to analyze on basis of one or more moral theories of their own choice. At the end

of the course, students were asked to list their most preferred moral theory and to explain

their reasons behind this choice. While the students’ rationales are not reviewed in this

article, an overview of the preferences below is presented (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1: Students’ Preference for a Moral Theory

Figure 1: Students’ Preference for a Moral Theory

Based on the above-listed preferences, the author decided to engage in some deliberations

on the two most popular theories as are presented next.

Universalism: A Consistency-Based Moral Approach

Moral Philosophy

No. of Students

Utilitarianism

79

Universalism

46

Virtue Ethics

13

Golden rule

11

Ethical Egoism

9

Divine Command theory

5

Total

163

0

20

40

60

80

Undergraduate & Graduate Business

Students' preference for a moral theory

Students

3

The Universalist approach, as it is most frequently discussed in our times, was mainly

developed by Immanuel Kant, a German philosopher who lived in the 18

th

century (1724–

1804). Universalism is considered a deontological or duty-based approach (Weiss, 2009).

Strict and responsible by nature and through education and upbringing, Kant’s philosophy

was centered on human autonomy. The notion of autonomy should be interpreted here as

formulating our own law on basis of our understanding and the framework of our

experiences. Being self-conscious — and thus aware of the reasons behind our actions — is

therefore one of the highest principles of Kant’s theoretical philosophy (Rolf, 2010). Kant

felt that one’s moral philosophy should be based on autonomy. In his opinion, there should

be one universal moral law which we should independently impose onto ourselves. He

named it the “categorical imperative.”

The categorical imperative holds that every act we commit should be based on our personal

principles or rules. Kant refers to these principles or rules as “maxims.” Maxims are

basically the “why” behind our actions. Even if we are not always aware of our maxims, they

are there to serve the goals we aim to achieve. In order to ensure that our maxims are

morally sound, we should always ask ourselves if we would want them to be universal laws.

In other words, would our maxim pass the test of universalizability? Within the framework of

the categorical imperative, a maxim should only be considered permissible if it could

become a universal law. If not, it should be dismissed (Rolf, 2010). “Kant also emphasized

the importance of respecting other persons, which has become a key principle in modern

Western philosophy. According to Kant, ‘Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own

person or that of another, always as an end and never as a means only’” (Johnson, 2012, p.

159). Shining some clarifying light on the above, Weiss (2009) affirms that the categorical

imperative consists of two parts: 1) We should only choose for an act if we would want every

person on earth, being in the same situation as we currently are, to act in exactly the same

way, and 2) We should always act in a way that demonstrates respect to others and treats

them as ends onto themselves rather than as means toward an end.” A swift and effective

way to measure the moral degree of our maxims is to consider ourselves or a dearly loved

one at the receiving end of our actions: would we still want to apply them? If not, then we

should rethink them.

Most Important Strengths of Universalism

The most obvious strength of Universalism is its consistency. With this moral approach,

there is no question about the decision to be made: what is right for one should be right for

all. This redacts any emotional considerations and guarantees a clearly-outlined modus

operandi.

Another major strength of Universalism is the fact that this moral theory focuses on the

intentions of the decision maker, thus making him his own moral agent, and motivating him

to practice respect for those he encounters in his decision-making processes. Furthermore,

the reflective element in this theory, evoking a deep consideration for the well-being of all

parties involved in our actions, exalts it moral magnitude. Yang (2006) makes a strong

stance in favor of Kant’s categorical imperative (Universalism) and the fact that universality

of moral values should exist. Yang affirms, “Moral requirements have a special status in

human life. […] If one who has moral sentiments at all fails to act on them, one will feel

guilty, regretful, or ashamed. Moral requirements are the most demanding … standards for

conduct, for interpersonal and intercultural criticism” (pp. 127-128).

4

The foundational guideline in Universalism to make our counterparts an end onto

themselves instead of a means toward our ends reminds us somewhat of the Golden Rule,

The Golden Rule, however, could be considered as having a narrower focus than the

Universalist approach since it only considers immediate stakeholders while Universalism

urges us to think in terms of universalizability. Moyaert (2010) shares the opinion that

Kant’s categorical imperative can be seen as “a further formalization of the golden rule” (p.

455).

The fact that intentions are more important than outcomes in Universalism also emphasizes

its noble foundation. While we cannot influence the outcomes of our actions, we can, after

all, always embark upon their realization with the best of intentions.

Most Important Weaknesses of Universalism

It is first and foremost the aspect of universalizability that raises concern within the

opponents of the Universalist approach: how possible is it, they claim, to consider all people,

all nations, all beliefs, and all cultures in every single act we implement? In addition, the

equality-based approach, which Universalism proclaims, is an ideal one, but not a very

realistic one in today’s world. While a good point could be made in favor of ending unfair

treatment of those who are already privileged, there is a serious weakness to be detected if

we start applying equal treatment when we want to restore an existing imbalance. By

utilizing the Universalist approach at all times, we would not be able to correct existing

imbalances simply because Universalism does not condone a more favorable approach to

anyone — hence, not even to those that are oppressed and subjugated. Similarly, it does not

support a less favorable treatment of anyone — hence, not even those that have been

unfairly privileged in past centuries.

Contemplating the major moral issue of human rights, Kim (2012) raises an important

question by comparing the Divine Command theory, which proposes a Universalist approach

based on religious rulings, with Kant’s categorical imperative, which proposes this same

approach based on autonomy. What makes one more acceptable than the other if they are

both aiming for universal application? The fact that non-Muslims become uncomfortable

when a Muslim scholar claims that Islam has formulated fundamental rights for all of

humanity, and that these rights are granted by Allah, should be a clear indication that there

could be opponents to any universal law formulated by any group or individual at any time.

“The question here is whether two conflicting justifications that appeal to different

foundations of human rights (divine command and autonomy) should strengthen or weaken

our confidence in the universality belief” (Kim, 2012, p. 263). In Kant’s favor, Robertson,

Morris, and Walter (2007) point out that the notion of autonomy assumes a rational

person’s capacity for free moral choice made in the spirit of enlightenment. They defend

Universalism as being secular and rational, free from superstition or divine commands, void

of emotions or filial bonds, and centered on doing the right thing for the right reasons.

Conversely, Robertson et. al. admit that Universalism, as Kant defined it, is void of

compassion, as it mainly focuses on fulfilling a responsibility. Indeed, rigid and consistent at

its core, the Universalist approach does not leave room for flexibility. What is right is right

and what is wrong is wrong: no negotiation is possible. This stance can become problematic

when situations occur with conflicting duties among involved parties, because in such cases

a mutually gratifying solution is impossible to attain.

5

The intention-based focus of Universalism may not always lead to desired outcomes and

may leave unwanted victims down the line. This could be seen as an unwelcome side effect

of a generally well-considered moral approach. No one enjoys disastrous outcomes, even if

intentions were good. Universalism may therefore not always be the most desired mindset,

depending on what is at stake.

Critical Opportunities for Universalism

Possible opportunities for Universalism need to be considered against the backdrop of

contemporary society. Given the upward trend of globalization and the consequentially

increasing cultural blend of people worldwide, the mindset of Universalism may become

more appealing in near future moral considerations. The increased exposure to a broad

range of cultures, religions, ethnicities, age groups, and education levels in one single work

environment, has become part of the fabric of modern day’s workplaces. Universalists feel

that “Our globally interdependent world […] stands in need of an ethical perspective that

transcends cultural and religious differences” (Moyaert, 2010, p. 440). If this mindset finds

acceptance on a massive global scale, Universalist thinking may become the most gratifying

and acceptable — hence, the dominant moral philosophy.

Critical Threats for Universalism

Inasmuch as globalization is an unstoppable trend, the diversity that it brings reinforces

flexibility and receptiveness to multiple perceptions. In its conceptual form, Universalism is

known as a rigid, inflexible moral stance. The twenty-first century has taught us thus far that

such inflexibility cannot be upheld and tolerated in today’s versatile environments. While

there is much to be said about considering others as ends unto themselves and not as

means toward our ends, the manifestation of conflicting duties based on opposing

viewpoints is also more pertinent than ever. This may either lead to an opportunity for

Universalism to be adjusted toward contemporary needs of human society, or to

obsolescence of a once laudable moral theory. Figure 2, below, presents the above-

mentioned SWOT analysis for Universalism in a nutshell.

6

Utilitarianism: A Consequence-Based Approach

Utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism, which entails that the end result (the

“consequence”) should be the most important consideration in any act implemented. The

consequentialist approach, therefore, forms a stark contrast with the deontological

(Universalist) approach discussed earlier, because Universalism focuses on intentions rather

than outcomes while consequentialism, and therefore Utilitarianism, focuses on outcomes

rather than intentions. “[W]hether an act is morally right [in this theory] depends only on

consequences (as opposed to the circumstances or the intrinsic nature of the act or

anything that happens before the act)” (Sinnot-Armstrong, 2011, ¶ 3).

In general, Utilitarianism holds the view that the action that produces the greatest wellbeing

for the largest number is the morally right one. “On the Utilitarian view one ought to

maximize the overall good — that is, consider the good of others as well as one’s own good”

(Driver, 2009, ¶ 2). Using more economic-oriented terms, Robertson, Morris, & Walter

(2007) define Utilitarianism as “a measure of the relative happiness or satisfaction of a

group, usually considered in questions of the allocation of limited resources to a population”

(p. 403). Two of the most noted Utilitarian advocates, Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873 — a follower of Bentham), felt that “the good” needed to be

maximized to benefit as many stakeholders as possible. Bentham and Mill are considered

the classical Utilitarians. They were major proponents of constructive reforms in the legal

and social realm which explains why they promoted the stance of “the greatest amount of

good for the greatest number” (Driver, ¶ 3). Bentham, for instance, was convinced that

some laws were bad due to their lack of utility which gave rise to mounting societal

despondency without any compensating happiness. He felt, much to the surprise of many of

his contemporaries, that the quality of any act should be measured by its outcomes. This

was, of course, a very instrumental-based mindset, as it was mainly concerned with tangible

results.

Due to Bentham’s focus on the happiness levels of the largest group, there was a significant

degree of flexibility embedded in the Utilitarian approach. After all, whatever is considered a

cause for general happiness today may not be seen as such tomorrow. Tastes, perceptions,

needs, and social constructs change, and “the greatest good for the greatest number” may

look entirely different tomorrow than it does today.

Johnson (2012) posits that there are four steps to conduct a Utilitarian analysis of an ethical

problem: 1) Identifying the issue at hand; 2) Considering all groups, immediate and non-

immediate, that may be affected by this issue; 3) Determining the good and bad

consequences for those involved; and 4) Summing the good and bad consequences and

selecting the option of which the benefits outweigh the costs.

Weiss (2009) emphasizes that there are two types of criteria to be considered in

Utilitarianism: rule-base and act-based. Rule-based Utilitarians consider general rules to

measure the utility of any act, but are not fixated on the act itself. As an example, while a

rule-based Utilitarian may honor the general principle of not-stealing, there may be another

principle under certain circumstances that serve a greater good, thus override this principle.

Act-based Utilitarians consider the value of their act, even though it may not be in line with a

general code of honor. If, for instance, an act-based Utilitarian considers a chemical in his

workplace harmful for a large group of people, he may decide to steal it and discard it,

7

considering that he saved a large group of people, even though he engaged in the acts of

stealing and destroying company property.

Most Important Strengths of Utilitarianism

The most important appeal of the Utilitarian approach is its focus on the wellbeing of the

majority, thus ensuring a broadminded, social approach to any problem that arises. This

theory also overrules selfish considerations and requires caution in decision-making

processes — with a meticulous focus on the possible outcomes.

In addition, the flexibility that is embedded in this approach makes it easy to reconsider and

adjust decision-making processes based on current circumstances. As we live in an era

where flexibility is the mantra for succeeding, Utilitarianism seems to be a solid way of

ensuring that needs are met with consideration of the needs and desires of all stakeholders.

Robertson, Morris, and Walter (2007) underscore this as follows: “The advantages of

Utilitarianism as an ethical theory lie in its intuitive appeal, particularly in the case of ‘act

Utilitarianism,’ and its apparent scientific approach to ethical reasoning” (p. 404).

Most Important Weaknesses of Utilitarianism

When adhering to the Utilitarian (consequentialist) approach, one should be willing to let the

general welfare prevail and thus be ready to denounce personal moral beliefs and integrity

in case these are not aligned with what is considered “the overall good.” Volkman (2010)

raises a strong point to ponder in this matter: “One’s integrity cannot be simply weighed

against other considerations as if it was something commensurable with them. Being

prepared to do that is already to say one will be whatever the Utilitarian standard says one

must be, which is to have already abandoned one’s integrity” (p. 386). Illustrating the moral

dilemma that may rise between a potentially questionable “common good” and one’s

personal moral beliefs, Robertson, Morris and Walter (2007) discuss the so-called

“replaceability” problem. Within the Utilitarian mindset, it would be preferable to kill one

healthy person in order to provide transplant organs for six others, or to kill one man in order

to save dozens of others.

Another point of caution within the Utilitarian approach is its outcome focus; while the end-

result may be considered admirable for any decision, there is no guarantee that an act will

actually generate a desired outcome. Life is unpredictable, and with the growing complexity

of our current work environments, there may be many factors we overlook. This can lead to

undesired outcomes that backfire, regardless of the initial focus. If, for instance, a manager

decides to layoff three employees to reduce overhead and save the livelihood of twenty

other workers, he may find that several of the twenty remaining workers either become

demoralized and less productive as a result of this decision or even resign if they have the

opportunity to do so.

In addition, Utilitarianism is an individual perception-based approach. Depending on the

magnitude of factors involved, it may occur that different Utilitarian decision makers come

to different conclusions and make entirely different outcomes based on the angle from

where they perceived the issue at hand. One manager may, for instance, conclude that

using secret data from a competitor brings the greatest good for the greatest number in

focusing on his workforce, leading him to use the data; while another manager may find that

8

using this secret data will negatively affect the well-being of the much larger workforce of his

competitor, leading him not to use it.

Critical Opportunities for Utilitarianism

Given its focus on circumstances at hand and its lack of concern about consistency, the

Utilitarian approach may remain a popular moral stance for a long time to come. Its

prominence may even rise due to the fact that societies are increasingly diversifying. Thus, it

is in need of continuous changing considerations of what is the proper moral decision.

Critical Threats for Utilitarianism

The lack of consistency, not only seen over time, but also in the decision-making processes

from various Utilitarians simultaneously, based on their viewpoints and the information they

have at hand, may become an increasing source of concern — leading to outcomes that

bring more harm than advantage to a community. “The greatest good for the greatest

number” is not as generally established as it may seem, but is a very personal perspective.

Figure 3 below presents the above-mentioned SWOT analysis for Utilitarianism in a nutshell.

Universalism and Utilitarianism: A Brief Comparison

As may have already become apparent, the Universalist and the Utilitarian approaches are

each other’s opposites in many regards. Where the Universalist approach focuses on good

intentions and discourages using anyone as a means toward our ends, the Utilitarian

approach focuses on good outcomes. This signifies that others may have to be used as a

means toward the desired end. While the Universalist approach emphasizes consistency at

all times through its universalizability underpinning, the Utilitarian approach supports

flexibility and thus, different decisions are based on the needs and circumstances at hand.

Yet, there are some foundational similarities in these two theories as well. Both aim to

eliminate selfish decision-making: the Universalist approach does so by refraining from

9

considering others as a means toward our selfish ends while the Utilitarian approach does

so by considering the greatest good for the greatest number of people involved. Both

theories perceive an attitude of universal impartiality as a foundational requirement. “On

this view, it is irrational to cast one’s self as an exception to some universal rule or policy

without some justification, since that would involve asserting an arbitrary difference”

(Volkman, 2010, p. 384).

On a less positive note, both theories share the weakness of undesirable outcomes. The

Universalist approach does so by being intention-based, and good intentions don’t

necessarily lead to good outcomes. The Utilitarian approach does so by focusing on

outcomes that may nonetheless turn out to be different from what was planned due to

insufficient data, unexpected turns in the circumstances, or the uncertainty of life.

Both theories remain prominent, regardless of their weaknesses, and both have the

potential of gaining even more appeal due to the trend of globalization and thus an

increasingly interwoven world: the Universalist approach due to its “universalizability” test,

which may not seem so far-fetched as the world continues to become a global village, and

the Utilitarian approach due to its flexibility, which may continue to gain attraction in

diversifying environments.

Conclusion

As can be derived from the two analyses, both theories have significant strengths and

weaknesses that make them difficult to apply unconditionally. As emotional beings, we don’t

make our moral decisions solely on basis of rationale. There is little doubt that even the

most steadfast Kantian Universalist will think twice before adhering to doing the right thing

at all times. If, for instance, a murderer would ask this Universalist where his children reside

so that he can go and take their lives, it will be highly doubtful that he will provide the

requested information — even if being honest is considered the right thing at all times and

even though he should see the murderer as an end onto himself and not as a means toward

a horrific end. This graphic example may illustrate that there are circumstances where we

will feel that it is morally more responsible to do the wrong thing for the right reasons

instead of doing the right thing for the wrong reasons.

Considering the contemporary world of interconnectedness and globalization, there have

been several authors in recent years who discussed converging moral prototypes to bridge

the discrepancy that exists between these two leading theories. Audi (2007), for instance,

proposes a model that combines the critical elements of virtue theories, Universalism and

Utilitarianism. Referring to this model as “pluralistic Universalism,” Audi focuses on three

central tenets that both theories harbor: wellbeing, justice, and freedom. In his pluralistic

Universalism model, Audi explains that mature moral agents should be able to make

morally-sound decisions that optimize happiness, maintain justice and freedom, and are

motivating. While generally advocating Audi’s theory, Strahovnik (2009) critiques that it is

vague and indeterminate and that it should include a list of prima facie duties including

refraining from harming, lying, breaking promises, and unjust treatment; correcting

wrongdoing; doing well to others; being grateful; improving ourselves; preserving freedom;

and showing respect. Strahovnik feels that, with the incorporation of these values, pluralistic

Universalism could emerge into a global ethic.

10

Whether any form of universal moral stance could ever be enforced remains to be seen. As

matters currently stand, our global human community — while converging through social

networks, increased travel, and worldwide professional shifts — still holds too much

perceptual, moral, religious, and cultural divergence to seriously strive for a global ethic. And

why should this be anyway? Pluralism is the spice of life and serves as the foundation to

keep us thinking critically about the various notions of “right” and “wrong” that currently

exist. As long as human beings have divergent mental models which they develop through

the multiplicity of impressions they acquire throughout their lives, they will continue to differ

in perspectives. Rather than developing a moral doctrine that we are all supposed to honor,

we should consider, within reasonable, compassionate boundaries, the healthy dialogues

and the perceptional expansion that results from diversity. In the end, there is still no

stronger and more direct response to any ethical dilemma than the three golden questions

posted in the introductory part of this article:

(1) Would I still do this if it would be published in tomorrow’s newspaper?

(2) Would I still do this if my family would know about it?

(3) Would I still do this if my child (or another loved one) would be on the receiving end?

If the answer is “yes” on all three counts, the act is most likely one that we will be able to

live with without regrets.

And is that not what ultimately matters?

References

Audi, R. (2007). Moral Value and Human Diversity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Driver, J. (Summer, 2009). The history of utilitarianism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Retrieved on 19 July 2013 from http://plato.stanford.

edu/archives/sum2009/entries/Utilitarianism-history/.

Johnson, C. (2012). Meeting the Ethical Challenges of Leadership: Casting Light or Shadow

(4

th

ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kim, E. (2012). Justifying human rights: Does consensus matter? Human Rights Review,

13(3), 261-278.

Moyaert, M. (2010). Ricœœur on the (im)possibility of a global ethic towards an ethic of

fragile interreligious compromises. Neue Zeitschrift Für Systematische Theologie Und

Religionsphilosophie, 52(4), 440-461.

Rolf, M. (Fall 2010). Immanuel Kant. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N.

Zalta (ed.). Retrieved on 18 July 2013 from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant/.

Weiss, J. W. (2009). Business Ethics: A Stakeholder & Issues Management Approach.

Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

Robertson, M., Morris, K., & Walter, G. (2007). Overview of psychiatric ethics V: Utilitarianism

and the ethics of duty. Australasian Psychiatry, 15(5), 402-410.

11

Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (Winter 2012). Consequentialism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Retrieved on 19 July 2013 from http://plato.stanford.

edu/archives/win2012/entries/consequentialism/.

Strahovnik, V. (2009). Globalization, globalized ethics and moral theory. Synthesis

Philosophica, 24:2(48), 209-218.

Volkman, R. (2010). Why information ethics must begin with virtue ethics. Metaphilosophy,

41(3), 380-401.

Yang, X. (2006). Categorical imperatives, moral requirements, and moral motivation.

Metaphilosophy, 37(1), 112-129.

About the Author

Joan Marques, PhD, EdD, serves as Assistant Dean of Woodbury University’s School of

Business, Chair and Director of the BBA Program, and Professor of Management. She holds

a PhD from Tilburg University and an Ed.D. from Pepperdine University’s Graduate School of

Education and Psychology, an MBA from Woodbury University, and a BSc in Business

Economics from MOC, Suriname. She also holds an AACSB Bridge to Business Post-Doctoral

Certificate from Tulane University’s Freeman School of Business. Her teaching and research

interests focus on workplace spirituality, ethical leadership, and leadership awareness. She

has been widely published in scholarly as well as practitioner based journals, and has

authored/co-authored more than 16 books on management and leadership topics.